United States involvement in regime change

United States involvement in regime change has entailed both overt and covert actions aimed at altering, replacing, or preserving foreign governments. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. government initiated actions for regime change mainly in Latin America and the southwest Pacific, including the Spanish–American and Philippine–American wars. At the onset of the 20th century, the United States shaped or installed governments in many countries around the world, including neighbors Panama, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.

During World War II, the United States helped overthrow many Nazi Germany or imperial Japanese puppet regimes. Examples include regimes in the Philippines, Korea, the Eastern portion of China, and much of Europe. United States forces were also instrumental in ending the rule of Adolf Hitler over Germany and of Benito Mussolini over Italy. After World War II, the United States in 1945 ratified[1] the UN Charter, the preeminent international law document,[2] which legally bound the U.S. government to the Charter's provisions, including Article 2(4), which prohibits the threat or use of force in international relations, except in very limited circumstances.[3] Therefore, any legal claim advanced to justify regime change by a foreign power carries a particularly heavy burden.[4]

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. government struggled with the Soviet Union for global leadership, influence and security within the context of the Cold War. Under the Eisenhower administration, the U.S. government feared that national security would be compromised by governments propped by the Soviet Union's own involvement in regime change and promoted the domino theory, with later presidents following Eisenhower's precedent.[5] Subsequently, the United States expanded the geographic scope of its actions beyond traditional area of operations, Central America and the Caribbean. Significant operations included the United States and United Kingdom-orchestrated 1953 Iranian coup d'état, the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion targeting Cuba, and support for the overthrow of Sukarno by General Suharto in Indonesia. In addition, the U.S. has interfered in the national elections of countries, including in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, the Philippines in 1953, and in Lebanon in the 1957 elections using secret cash infusions.[6] According to one study, the U.S. performed at least 81 overt and covert known interventions in foreign elections during the period 1946–2000.[7] Another study found that the U.S. engaged in 64 covert and six overt attempts at regime change during the Cold War.[5]

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States has led or supported wars to determine the governance of a number of countries. Stated U.S. aims in these conflicts have included fighting the War on Terror, as in the ongoing Afghan war, or removing dictatorial and hostile regimes, as in the Iraq War.

Pre-1887 interventions[edit]

1800s[edit]

1805: Tripolitania[edit]

The United States had been at war with Ottoman Tripolitania to stop them from capturing United States ships and enslaving crew members from the United States. The United States blockade had been ineffective at getting the Pasha of Tripoli, Yusef Karamanli, to surrender, and the United States had suffered a number of military defeats. So the United States decided to try a new tactic. William Eaton, was given permission to and appointed by Thomas Jefferson, to lead troops from Alexandria, into Tripolitania to try and put up Karamanli's exiled brother, Hamet Karamanli, as the Pasha. Eaton's troops were a combination of US soldiers and hired mercenaries, along with Hamet.[8] He led them into the Battle of Derna, and won a victory capturing Derna, turning the war in US favor. Under pressure, Yusef met with State Department diplomats, and agreed to release the slaves for a ransom.[9] Despite protest from Eaton this agreement went through, and Hamet was forced to return to Egypt. William Eaton felt betrayed by the decision.[10]

1846-1848 Annexation of Texas and invasion of California[edit]

The United States annexed the Republic of Texas, at the time considered by Mexico to be a rebellious province of Mexico.[11] During the war with Mexico that ensued, the United States seized California from Mexico.[12]

1860s[edit]

1865–1867: Mexico[edit]

While the United States was in the American Civil War, France, and other countries, took the opportunity to invade Mexico, to collect debts. France then installed Habsburg prince Maximilian I as the Emperor of Mexico. After the Civil war ended the United States began supporting the Liberal forces of Benito Juarez against the forces of Maximilian. The United States began sending and dropping arms into Mexico and many Americans fought alongside Juarez. Eventually, Juarez and the Liberals took back power and executed Maximillian I.[13][14][15] The United States was against it and had invoked the Monroe Doctrine. William Seward even said afterwards "The Monroe Doctrine, which eight years ago was merely a theory, is now an irreversible fact."[16]

1887–1912: U.S. Empire, Expansionism, and the Roosevelt Administration[edit]

1880s[edit]

1887–1889: Samoa[edit]

In the 1880s, Samoa was a monarchy with two rival claimants to the throne, Malietoa Laupepa or Mata'afa Iosefo. The Samoan crisis was a confrontation between the United States, Germany and Great Britain from 1887 to 1889, with the powers backing rival claimants to the throne of the Samoan Islands which became the First Samoan Civil War.[17] The powers eventually agreed that Laupepa would become king. After the powers withdrew, the civil war went on until 1894, when Laupepa secured his power.

1890s[edit]

1893: Kingdom of Hawaii[edit]

Anti-monarchs, mostly Americans, in Hawaii, engineered the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii. On January 17, 1893, the native monarch, Queen Lili'uokalani, was overthrown. Hawaii was initially reconstituted as an independent republic, but the ultimate goal of the action was the annexation of the islands to the United States, which was finally accomplished in 1898.

1900s[edit]

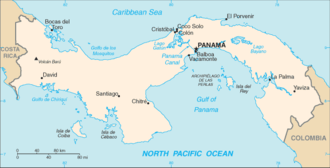

1903: Panama[edit]

In 1903, the U.S. aided the secession of Panama from the Republic of Colombia. The secession was engineered by a Panamanian faction backed by the Panama Canal Company, a French–US corporation whose aim was the construction of a waterway across the Isthmus of Panama thus connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. In 1903, the U.S. signed the Hay-Herrán Treaty with Colombia, granting the United States use of the Isthmus of Panama in exchange for financial compensation.[18][19] amidst the Thousand Days' War. The Panama Canal was already under construction, and the Panama Canal Zone was carved out and placed under United States sovereignty. The US did not transfer the zone back to Panama until 2000.

1903–1925: Honduras[edit]

In what became known as the "Banana Wars," between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934, the U.S. staged many military invasions and interventions in Central America and the Caribbean.[20] The United States Marine Corps, which most often fought these wars, developed a manual called The Strategy and Tactics of Small Wars in 1921 based on its experiences. On occasion, the Navy provided gunfire support and Army troops were also used. The United Fruit Company and Standard Fruit Company dominated Honduras' key banana export sector and associated land holdings and railways. The U.S. staged invasions and incursions of US troops in 1903 (supporting a coup by Manuel Bonilla), 1907 (supporting Bonilla against a Nicaraguan-backed coup), 1911 and 1912 (defending the regime of Miguel R. Davila from an uprising), 1919 (peacekeeping during a civil war, and installing the caretaker government of Francisco Bográn), 1920 (defending the Bográn regime from a general strike), 1924 (defending the regime of Rafael López Gutiérrez from an uprising) and 1925 (defending the elected government of Miguel Paz Barahona) to defend US interests.[21] Writer O. Henry coined the term "Banana republic" in 1904 to describe Honduras.

1906–1909: Cuba[edit]

After the explosion of The Maine the United States declared war on Spain, starting the Spanish–American War.[22] The United States invaded and occupied Spanish-ruled Cuba in 1898. Many in the United States did not want to annex Cuba and passed the Teller Amendment, forbidding annexation. Cuba was occupied by the U.S. run by military governor Leonard Wood during the first occupation from 1898–1902, after the end of the war. The Platt Amendment was passed later on outlining U.S. Cuban relations. It said the U.S. could intervene anytime against a government that was not approved, forced Cuba to accept U.S. influence, and limited Cuban abilities to make foreign relations.[23] The United States forced Cuba to accept the terms of the Platt Amendment, by putting it into their constitution.[24] After the occupation, Cuba and the U.S. would sign the Cuban-American Treaty of Relations in 1903, further agreeing to the terms of the Platt Amendment.[25]

Tomás Estrada Palma became the first president of Cuba after the U.S. withdrew. He was a member of the Republican Party of Havana. He was re-elected in 1905 unopposed, however, the Liberals accused him of electoral fraud. Fighting began between the Liberals and Republicans. Due to the tensions he resigned on September 28, 1906, and his government collapsed soon afterwards. U.S. Secretary of State William Howard Taft invoked the Platt Amendment and the 1903 treaty, under approval of Theodore Roosevelt, invading the country, and occupying it. The country would be governed by Charles Edward Magoon during the occupation. They oversaw the election of Jose Miguel Gomez in 1909, and afterwards withdrew from the country.[26]

1909–1910: Nicaragua[edit]

Governor Juan Jose Estrada, member of the conservative party, led a revolt against the president, Jose Santos Zelaya, member of the liberal party. This became what is known as the Estrada's Rebellion. The United States supported the conservative forces, because Zelaya had wanted to work with Germany or Japan to build a new canal through the country. The U.S. controlled the Panama Canal, and did not want competition from another country outside of the Americas. Thomas P Moffat, a US council in Bluefields, Nicaragua would give overt support, in conflict with the US trying to only give covert support. Direct intervention would be pushed by the secretary of state Philander Knox. Two Americans were executed by Zelaya for their participation with the conservatives. Seeing an opportunity the United States became directly involved in the rebellion and sent in troops, which landed on the Caribbean coast. On December 14, 1909 Zelaya was forced to resign under diplomatic pressure from America and fled Nicaragua. Before Zelaya fled, he along with the liberal assembly choose Jose Madriz to lead Nicaragua. The U.S. refused to recognize Madriz. The conservatives eventually beat back the liberals and forced Madriz to resign. Estrada then became the president. Thomas C Dawson was sent as a special agent to the country and determined that any election held would bring the liberals into power, so had Estrada set up a constituent assembly to elect him instead. In August 1910 Estrada became president of Nicaragua under U.S. recognition, agreeing to certain conditions from the U.S. After the intervention, the U.S. and Nicaragua signed a treaty on June 6, 1911.[27][28][29]

1912–1941: The Wilson administration, World War I, and the interwar period[edit]

1910s[edit]

1912–1933: Nicaragua[edit]

In the years after the Estrada rebellion, conflict between the liberals and conservatives continued. U.S. loans and business were under threat. Estrada was forced to resign by the Minister of War General Luis Mena and conservative Vice President Adolfo Diaz replaced him. Diaz was aligned with the U.S. and this made him unpopular with the Nicaraguan populace and Mena. Mena forced the cabinet to name him the successor to Diaz, but the U.S. did not recognize the decision. Due to this Mena led a rebellion with the liberals against Diaz declaring himself president of Nicaragua.

The Taft administration sent troops into Nicaragua and occupied the country. When the Wilson administration came into power, they extended the stay and took complete financial and governmental control of the country, leaving a heavily armed legation. U.S. president Calvin Coolidge removed troops from the country, leaving a legation and Adolfo Diaz in charge of the country. Rebels ended up capturing the town with the legation and Diaz requested troops came back, which they did a few months after leaving. The U.S. government fought against rebels led by Augusto Cesar Sandino. Franklin Delano Roosevelt pulled out because the U.S. could no longer afford to keep troops in the country due to the Great Depression. The second intervention in Nicaragua would become one of the longest wars in United States history. The United States left the US-friendly Somoza family in charge, and in 1934 they would kill Sandino.[30]

1913-1919: Mexico[edit]

During the Mexican revolution the USA helped to make the coup d'état of 1913, assassinating Francisco I. Madero. Later, in April 1914, the USA army invaded Veracruz and occupied it for 7 months. And later in 1916 USA invaded Mexico through the northern border in an attempt to kill Pancho Villa and his revolutionary army.

1915–1934: Haiti[edit]

The U.S. occupied Haiti from 1915 to 1934. U.S.-based banks had lent money to Haiti and the banks requested U.S. government intervention. In an example of "gunboat diplomacy," the U.S. sent its navy to intimidate to get its way.[31] Eventually, in 1917, the U.S. installed a new government and dictated the terms of a new Haitian constitution of 1917 that instituted changes that included an end to the prior ban on land ownership by non-Haitians. The Cacos (military group) were originally armed militias of formerly enslaved persons who rebelled and took control of mountainous areas following the Haitian Revolution in 1804. Such groups fought a guerrilla war against the U.S. occupation in what were known as the "Caco Wars."[32]

1916–1924: Dominican Republic[edit]

U.S. marines invaded the Dominican Republic and occupied it from 1916 to 1924, and this was preceded by US military interventions in 1903, 1904, and 1914. The US Navy installed its personnel in all key positions in government and controlled the Dominican army and police.[33] Within a couple of days, the constitutional president, Juan Isidro Jimenes, resigned.[34]

1917–1919: Germany[edit]

After the release of the Zimmermann Telegram the United States joined the First World War on April 6, 1917, declaring war on the German Empire.[35] The Wilson Administration made a requirement of surrender be the abdication of the Kaiser and the creation of a German Republic. Woodrow Wilson had made U.S. policy to "Make the World Safe for Democracy". Germany surrendered November 11, 1918.[36] Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated on November 28, 1918.[37] While the United States did not ratify it, the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 had much input from the United States. It mandated for Kaiser Wilhelm II to be removed from the government and tried, though the second part was never carried out.[38] Germany would then become the Weimar Republic. The United States signed the U.S.-German peace Treaty in 1921, solidifying the agreements made previously to the rest of the Entente with the U.S.[39]

1917–1920: Austria-Hungary[edit]

On December 7, 1917, the United States declared war on Austria-Hungary as part of World War I.[40] Austria-Hungary surrendered on November 3, 1918.[41] Austria became a republic and signed Treaty of Saint Germain in 1919 effectively dissolving Austria-Hungary.[42] The Treaty disallowed Austria to ever unite with Germany. Even though the United States had much effect on the treaty it did not ratify it and instead signed the U.S.-Austrian Peace Treaty in 1921, solidifying their new borders and government to the United States.[43] After brief civil strife, Hungary became a monarchy without a monarch, instead governed by a Regent. Hungary signed the Treaty of Trianon, in 1920 with the Entente, without the United States.[44] They signed the U.S.-Hungarian Peace Treaty in 1921 solidifying their status and borders with the United States.[45]

1918–1920: Russia[edit]

After the new Bolshevik government withdrew from World War I, the U.S. military together with forces of its Allies invaded Russia in 1918. Approximately 250,000 invading soldiers, including troops from Europe, the US and the Empire of Japan invaded Russia to aid the White Army against the Red Army of the new Soviet government in the Russian civil war. The invaders launched the North Russia invasion from Arkhangelsk and the Siberia invasion from Vladivostok. The invading forces included 13,000 U.S. troops whose mission after the end of World War I included the toppling of the new Soviet government and the restoration of the previous Tsarist regime. U.S. and other Western forces were unsuccessful in this aim and withdrew by 1920 but the Japanese military continued to occupy parts of Siberia until 1922 and the northern half of Sakhalin until 1925.[46]

1941–1945: World War II and the aftermath[edit]

1940s[edit]

1941: Panama[edit]

In 1931 Arnulfo Arias overthrew president Florencio Harmodio Arosemena and put his brother Harmodio Arias Madrid into power. In 1940, Arias became the president of Panama. While the United States had not yet entered the war, tensions were already increasing with the Axis. The United States knew that if war broke out, which it most likely would and did, the Panama canal would be strategically important and were worried about Arias being in power. The United States government used its contacts in the Panama National Guard, which the U.S. had earlier trained, to back a coup against the government of Panama in October 1941. The U.S. had requested that the government of Panama allow it to build over 130 new military installations inside and outside of the Panama Canal Zone, and the government of Panama refused this request at the price suggested by the U.S.[47] President Arnulfo Arias fled the country and Ricardo Adolfo de la Guardia Arango, the leader of the coup and a friend of the US government, became president.[48]

1941–1952: Japan[edit]

After the Allied victory in World War 2, Japan was occupied by Allied forces under the command of Douglas MacArthur. In 1946, the Japanese Diet ratified a new Constitution of Japan that followed closely a 'model copy' prepared by MacArthur's command,[49] and was promulgated as an amendment to the old Prussian-style Meiji Constitution. The constitution renounced aggressive war and was accompanied by liberalization of many areas of Japanese life.

While liberalizing life for most Japanese, the Allies tried many Japanese war criminals and executed some, while granting amnesty to the family of Emperor Hirohito.[50]

The occupation was ended by the Treaty of San Francisco.[50]

Following the United States invasion of Okinawa during WWII, the U.S. installed the United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands. Pursuant to a treaty with the Japanese government,[citation needed] in 1950 the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands took over and ruled Okinawa and the rest of the Ryukyu Islands until 1972. During this "trusteeship rule," the U.S. built numerous military bases, including bases that operated nuclear weapons. U.S. rule was opposed by many local residents, creating the Ryukyu independence movement that struggled against U.S. rule.

1941–1949: Germany[edit]

The United States took part in the Denazification of the Western portion of Germany. Former Nazis were subjected to varying levels of punishment, depending on what the US thought of their levels of guilt. Eisenhower initially estimated that the process would take 50 years.[51] Depending on a former Nazi's level of culpability, punishments could range from a fine (for those judged least culpable), to denial of permission to work as anything but a manual laborer, to imprisonment and even death for the most severe offenders, such as those convicted in the Nuremberg Trials. At the end of 1947, for example, the Allies held 90,000 Nazis in detention; another 1,900,000 were forbidden to work as anything but manual laborers.[52]

As Germans took more and more responsibility for Germany, they pushed for an end to the denazification process, and the Americans allowed this. In 1949, the Federal Republic of Germany, also known as West Germany, was formed and took responsibility for denazification. For most former Nazis, the process came to an end with amnesty laws passed in 1951.[53] The ultimate outcome of denazification was the creation of a parliamentary democracy in West Germany.[54]

1941–1946: Italy[edit]

In July–August 1943, the US participated in the Allied invasion of Sicily, spearheaded by the U.S. Seventh Army, under Lieutenant General George S. Patton, in which over 2000 US servicemen were killed,[55] initiating the Italian Campaign which conquered Italy from the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini and its Nazi German allies. Mussolini was arrested by order of King Victor Emmanuel III, provoking a civil war. The king appointed Pietro Badoglio as new Prime Minister. Badoglio stripped away the final elements of Fascist rule by banning the National Fascist Party, then signed an armistice with the Allied armed forces. Italy's military outside of the peninsula itself collapsed, its occupied and annexed territories fell under German control. Italy capitulated to the Allies on 3 September 1943. The northern half of the country was occupied by the Germans with help from Italian fascists and made a collaborationist puppet state, while the south was governed by monarchist forces, which fought for the Allied cause as the Italian Co-Belligerent Army.[56] Partisans (many former Royal Italian Army soldiers) of disparate political ideologies operated all over Italy. Rome was taken in June 1944. In April 1945, the Italian Partisans' Committee of Liberation declared a general uprising. On 28 April 1945, Benito Mussolini was executed by Italian partisans, two days before Adolf Hitler's suicide, the Germans surrendered Italy. There followed a rapid succession of anti-fascist prime ministers, the abdication of the King in May 1946, the one-month reign of Umberto II, the 1946 Italian institutional referendum which brought monarchy to an end and inaugurated the current Italian Republic and the 1946 Italian general election won by Christian Democrats.

1944–1946: France[edit]

British, Canadian and United States forces were the critical participants in Operation Goodwood and Operation Cobra, leading to a military breakout which ended the Nazi occupation of France. The actual Liberation of Paris was accomplished by French forces. The French formed the Provisional Government of the French Republic in 1944, leading to the formation of the French Fourth Republic in 1946.

The liberation of France is celebrated regularly up to the present day.[57][58]

1944–1945: Belgium[edit]

In the wake of the 1940 invasion, Germany established the Reichskommissariat of Belgium and Northern France to govern Belgium. United States, Canadian, British, and other Allied forces ended the Nazi occupation of most of Belgium in September 1944. The Belgian Government in Exile under Prime Minister Hubert Pierlot returned on 8 September.[59]

In December, American forces suffered over 80,000 casualties defending Belgium from a German counterattack in the Battle of the Bulge. By February 1945, all of Belgium was in Allied hands.[60]

The year 1945 was chaotic. Pierlot resigned, and Achille Van Acker of the Belgian Socialist Party formed a new government. There were riots over the Royal Question—the return of King Leopold III. Although the war continued, Belgians were again in control of their own country.[61]

1944–1945: Netherlands[edit]

During the Nazi occupation, the Netherlands was governed by the Reichskommissariat Niederlande, headed by Arthur Seyss-Inquart. British, Canadian, and American forces liberated portions of the Netherlands in September 1944. However, after the failure of Operation Market Garden, the liberation of the largest cities had to wait until the last weeks of the European war. The occupied portions of the Netherlands suffered a famine that Winter. British and American forces crossed the Rhine on 23 March 1945, and Canadian forces in their wake then entered the Netherlands from the East. The remaining German forces in the Netherlands surrendered on 5 May, which is celebrated as Liberation Day in the Netherlands. Queen Wilhelmina returned on 2 May, and elections were held in 1946, leading to a new government headed by Louis Beel.[62][63]

1944–1945: Philippines[edit]

United States landings in 1944 ended the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.[64] After the Japanese were defeated, the United States fulfilled a wartime promise by granting independence to the Philippines. Sergio Osmeña formed a Filipino government.

1945–1955: Austria[edit]

Austria was annexed to Germany in the 1938 Anschluss. As German citizens, many Austrians fought on the side of Germany during World War 2. After the Allied victory, the Allies treated Austria as a victim of Nazi aggression, rather than as a perpetrator. The United States Marshall Plan provided aid.[65]

The 1955 Austrian State Treaty re-established Austria as a free, democratic, and sovereign state. It was signed by representatives of the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France. It provided for the withdrawal of all occupying troops and guaranteed Austrian neutrality in the Cold War.[66]

1945–1991: The Cold War[edit]

1940s[edit]

1945–1948: South Korea[edit]

The Empire of Japan surrendered to the United States in August 1945, ending the Japanese rule of Korea. Under the leadership of Lyuh Woon-Hyung committees throughout Korea formed to coordinate transition to Korean independence. On August 28, 1945 these committees formed the temporary national government of Korea, naming it the People's Republic of Korea (PRK) a couple of weeks later.[67][68] On September 8, 1945, the United States government landed forces in Korea and thereafter established the United States Army Military Government in Korea (USAMGK) to govern Korea south of the 38th parallel north. The USAMGK outlawed the PRK government. The military governor Lieutenant-General John R. Hodge later said that "one of our missions was to break down this Communist government".[69][70]

In May 1948, Syngman Rhee, who had previously lived in the United States, won the election for president, which had been boycotted by most other politicians and in which voting was limited to property owners and tax payers or, in smaller towns, to town elders voting for everyone else.[71][72] Syngman Rhee, backed by the U.S. government, set up authoritarian rule that coordinated closely with big business and lasted until the 1980s.[73]

1945–1949: China[edit]

The U.S. government provided military, logistical and other aid to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) army led by Chiang Kai-shek in its civil war against the indigenous communist People's Liberation Army (PLA) led by Mao Zedong. Both the KMT and the PLA were fighting against Japanese occupation forces, until the Japanese surrender to the United States in August 1945. This surrender brought to an end the Japanese Puppet state of Manchukuo and the Japanese-dominated Wang Jingwei regime.[74]

After the Japanese surrender, the US continued to support the KMT against the PLA. The US airlifted many KMT troops from central China to Manchuria. Approximately 50,000 U.S. troops were sent to guard strategic sites in Hubei and Shandong. The U.S. trained and equipped KMT troops, and also transported Korean troops and even imperial Japanese troops back to help KMT forces fight, and ultimately lose, against the People's Liberation Army.[75] President Harry Truman justified deploying the very Japanese occupying army under whose boot the Chinese people had suffered so terribly to fight against the Chinese communists in this way: "It was perfectly clear to us that if we told the Japanese to lay down their arms immediately and march to the seaboard, the entire country would be taken over by the Communists. We therefore had to take the unusual step of using the enemy as a garrison until we could airlift Chinese National troops to South China and send Marines to guard the seaports."[76] Within less than two years after the Sino-Japanese War, the KMT had received $4.43 billion from the United States—most of which was military aid.[75][77]

1947–1949: Greece[edit]

By the Summer of 1944, Communist partisans, then known as the Greek People's Liberation Army (ELAS), had liberated nearly all of Greece outside of Athens from Axis occupation, while also attacking and defeating rival non-Communist partisan groups. On 12 August 1944, German forces retreated from the Athens area two days ahead of British landings there, ending the Axis occupation of Greece.

The British military together with Greek forces under control of the Greek government then fought for control of the country in the Greek Civil War against the Communists, who at that time were known as the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE). By early 1947, the British government could no longer afford the huge cost of financing the war against DSE, and pursuant to the October 1944 Percentages Agreement between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin, Greece was to remain part of the Western sphere of influence. Accordingly, the British requested the US government to step in and the U.S. flooded the country with military equipment, military advisers and weapons.[78]:553–554[79]:129[80][81] With increased U.S. military aid, by September 1949 the Greek government eventually won.[82]:616–617

1948: Costa Rica[edit]

1940s Costa Rica politics was dominated by Rafael Angel Calderon Guardia and his National Republican Party. Calderon was a right wing figure who had support of the Catholic Church and the elite. However he alienated the rich with his policies and attacked the German community present in the country.[83] Teodoro Picado Michalski was the successor of Calderon, and he strengthened the military, which was used to keep peace, and many forces aligned with the National Republican Party fought against the opposition. The National Republican Party, while right wing, had formed a coalition with the People's Vanguard Party, the Costa Rican communist party, led by congressmen Manuel Mora. Among those affected by the party was Jose Figueres Ferrer, a businessman who was exiled in 1942 for criticizing Calderon. He began training the Caribbean Legion hoping to overthrow authoritarian Latin American governments.[84][85][86][87][88] In the 1948 Costa Rican General Election the opposition candidate Otilio Ulate under the National Union Party won, however the Republicans with the communists decided to void the results.[89] This resulted into political chaos which would break out into the Costa Rican Civil War. This would begin when the National Liberation Army, formed and led by Figueres, exchanged fire with government troops.[90]

The US government kept an eye on the situation and became worried when the war broke out. Their main worry was Calderon's alliance with the communists, and the civil war had begun a little over a month after the 1948 Czechoslovak coup, which made the US more worried.[91] The US government also disliked Figueres, but would step in to help him indirectly, in order to destroy the influence of the communists. First, the US put the troops on the Panama canal on high alert to stop the communists in case they seized power, though they never invaded.[91] Second, and more importantly, while the Republicans was allied with the communists, they received assistance from right wing Nicaraguan dictator Anastascio Somoza Garcia, so the United States forced Somoza to stop supporting them. Thirdly the rebels received help from left wing Guatemalan president Juan Jose Arevalo, and when the Costa Rican government took the issue to the UN, the US stopped the issue from being addressed.[91] With this on April 24 the war ended with Figueres' rebels taking victory.

1949–1953: Albania[edit]

Albania was in chaos after World War II and the country was not as focused on peacetime conferences in comparison to other European nations, while having suffered high casualties.[92] It was threatened by its larger neighbors with annexation. After Yugoslavia dropped out of the East Bloc, the small country of Albania was geographically isolated from the rest of the East Bloc.

The United States and United Kingdom took advantage of the situation and recruited anti-communist Albanians who had fled after the USSR invaded. The US and UK formed the “Free Albania” National Committee, made up of many of the emigres. Albanians, recruited, were trained by the U.S. and UK., infiltrated the country, multiple times. Eventually, the operation was found out and many of the agents fled, were executed, or were tried. The operation would become a failure.The operation was declassified in 2006, due to the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act and is now available in the National Archives.[93][94]

1949: Syria[edit]

The democratically elected government of Shukri al-Quwatli was overthrown by a junta led by the Syrian Army chief of staff at the time, Husni al-Za'im, who became President of Syria on April 11, 1949. Za'im had extensive connections to CIA operatives,[95] although the exact nature of U.S. involvement in the coup remains highly controversial.[96][97][98] The construction of the Trans-Arabian Pipeline, which had been held up in the Syrian parliament, was approved by Za'im, the new president, just over a month after the coup.[99]

1950s[edit]

1950-1953: Korea[edit]

Ever since the Korean peninsula had been divided between the US and USSR, it had been hoped that the peninsula could be reunited under one government, though neither the US nor USSR wanted the other government in charge of it. During the conflict, both Korean governments considered themselves the legitimate government of Korea. The Southern government had crushed communist uprisings by the late '40s. However Kim Il-Sung thought that their military was weak and that the US would not defend them if he invaded. On June 25, 1950 the DPRK invaded the RoK exchanged fire and the DPRK quickly advanced to take much of the country.[100][101] However, Kim misjudged the US interest in who would control the peninsula. In 1949 the communists had won the Chinese Civil War and the US government did not want communism to expand further into Korea because administration officials such as Dean Acheson viewed communism through the lens of the Domino theory and George Kennan's idea of "containment".[102] The United States organized a vast coalition of armed forces and UN peacekeeping forces and pushed back against the DPRK.[103][104] General Douglas MacArthur advanced up the 38th Parallel on the Peninsula and intended to end the Northern government.[105][106] China joined the war and pushed the coalition forces back.[107] The war would continue until 1953 when an armistice was signed between both sides on July 23, 1953 ending the fighting and setting up the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).[108]

1952: Egypt[edit]

In February 1952, following January's violent riots in Cairo amid widespread nationalist discontent over the continued British occupation of the Suez Canal and Egypt's defeat in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, CIA officer Kermit Roosevelt Jr. was dispatched by the State Department to meet with Farouk I of the Kingdom of Egypt. American policy at that time was to convince Farouk to introduce reforms that would weaken the appeal of Egyptian radicals and stabilize Farouk's grip on power. The U.S. was notified in advance of the successful July coup led by nationalist and anti-communist Egyptian military officers (the "Free Officers") that replaced the Egyptian monarchy with the Republic of Egypt under the leadership of Mohamed Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser. CIA officer Miles Copeland Jr. recounted in his memoirs that Roosevelt helped coordinate the coup during three prior meetings with the plotters (including Nasser, the future Egyptian president); this has not been confirmed by declassified documents but is partially supported by circumstantial evidence. Roosevelt and several of the Egyptians said to have been present in these meetings denied Copeland's account; another U.S. official, William Lakeland, said its veracity is open to question. Hugh Wilford notes that "whether or not the CIA dealt directly with the Free Officers prior to their July 1952 coup, there was extensive secret American-Egyptian contact in the months after the revolution."[109][110]

1952-1953: Iran[edit]

From the discovery of oil in Iran in the late nineteenth century major powers exploited the weakness of the Iranian government to obtain concessions that many believed failed to give Iran a fair share of the profits. During World War II, the UK, the USSR and the US all became involved in Iranian affairs. Iranian officials began to notice that British taxes were increasing while royalties to Iran declined. By 1948, Britain received substantially more revenue from the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) than Iran. Negotiations to meet this and other Iranian concerns exacerbated rather than eased tensions.[111]

On March 15, 1951, the Majlis, the Iranian parliament, passed legislation championed by Mohammad Mosaddegh to nationalize the AIOC. The senate approved the measure two days later. Fifteen months later, Mosadegh was elected Prime Minister.

International business concerns then boycotted oil from the nationalized Iranian oil industry. This contributed to concerns in Britain and the US that Mosadegh might be a communist. He was reportedly supported by the Communist Tudeh Party.[112]

The CIA began supporting 18 of their favorite candidates in the 1952 Iranian Legislative Election.[113] After that the CIA launched Operation Ajax to restore the power of the Shah and crush the leftists. The 1953 Iranian coup d'état, (known in Iran as the "28 Mordad coup"[114]) was the overthrow of the democratically elected government of Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh on August 19, 1953, orchestrated by the intelligence agencies of the United Kingdom (under the name "Operation Boot") and the United States (under the name "TPAJAX Project").[115][116][117][118] The coup saw the transition of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi from a constitutional monarch to an authoritarian, who relied heavily on United States government support.

That support dissipated during the Iranian Revolution of 1979, as his own security forces refused to shoot into crowds of nonviolent protestors, which included family and friends of many in the security forces.[119]

1953-1958: Cuba[edit]

In July 1953 the 26th of July Movement rose up against Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista. The dictator had the support of the United States since he came to power and the US supplied him with planes, napalm, ships, tanks, and other military equipment as well as parts for these devices.[120] Despite this support as the insurgency intensified against Batista and they started gaining victories the U.S. turned against Batista and realized it did not look good that they were funding the losing unpopular side. The U.S. first tried gaining influence among the rebels by supplying them with "No less than $50,000" from 1957 to 1958.[121] Then in 1958 the United States imposed an arms embargo on Cuba stopping any military equipment from getting into the country. As well as equipment it ended the sale of parts used to fix equipment which especially effected the air force.[122] Despite the embargo U.S. businessmen and the Mafia still supported Batista.[123][124] However a year later in 1959 the revolutionaries won and took the country.

1953: Philippines[edit]

In the 1953 Philippines General Elections the CIA funded a number of candidates, including Ramon Magsaysay. The U.S. wanted the country secure in case China invaded. Magsaysay's campaign was run by Edward Lansdale on behalf of the CIA while other candidates competed for CIA influence and both major parties in the Philippines tried to nominate Marsaysay. Even the people of the Philippines were interested in the opinion of average Americans. The CIA involvement was very successful in getting their candidates elected.[125][126]

1954: Guatemala[edit]

In a CIA operation code named Operation PBSuccess, the U.S. government executed a coup that was successful in overthrowing the democratically elected government of President Jacobo Árbenz and installed Carlos Castillo Armas, the first of a line of right-wing dictators, in its place.[127][128][129] Not only was it done for the ideological purpose of containment, but the CIA had been approached by the United Fruit Company as it saw possible loss in profits due to the situation of workers in the country, i.e., the introduction of anti-exploitation laws.[130] The perceived success of the operation made it a model for future CIA operations because the CIA lied to the president of the United States when briefing him regarding the number of casualties.[131]

1956–1957: Syria[edit]

In 1956 Operation Straggle was a coup plot against Syria. The CIA made plans for a coup for late October 1956 to topple the Syrian government. The plan entailed takeover by the Syrian military of key cities and border crossings.[132][133][134] The plan was postponed when Israel invaded Egypt in October 1956 and US planners thought their operation would be unsuccessful at a time when the Arab world is fighting "Israeli aggression." The operation was uncovered and American plotters had to flee the country.[135]

In 1957 Operation Wappen was a coup plan against Syria. A second coup attempt the following year called for assassination of key senior Syrian officials, staged military incidents on the Syrian border to be blamed on Syria and then to be used as pretext for invasion by Iraqi and Jordanian troops, an intense US propaganda campaign targeting the Syrian population, and "sabotage, national conspiracies and various strong-arm activities" to be blamed on Damascus.[136][137][134][138] This operation failed when Syrian military officers paid off with millions of dollars in bribes to carry out the coup revealed the plot to Syrian intelligence. The U.S. Department of State denied accusation of a coup attempt and along with US media accused Syria of being a "satellite" of the USSR.[137][139][140]

There was also an assassination plot later, called "The Preferred Plan", in 1957 against many leaders in Syria. There would be a Free Syria committee set up and outside invasion would be encouraged. However, this plan was never put through.[141]

1957–1959: Indonesia[edit]

As a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement and host of the April 1955 Bandung Conference, Indonesia was charting a course toward an independent foreign policy that was not militarily committed to either side in the Cold War.[142][143] Starting in 1957, the CIA supported a failed coup plan by rebel Indonesian military officers. CIA pilots, such as Allen Lawrence Pope, piloted planes operated by CIA front organization Civil Air Transport (CAT) that bombed civilian and military targets in Indonesia. The CIA instructed CAT pilots to target commercial shipping in order to frighten foreign merchant ships away from Indonesian waters, thereby to weaken the Indonesian economy and thus to destabilize the government of Indonesia. The CIA aerial bombardment resulted in the sinking of several commercial ships[144] and the bombing of a marketplace that killed many civilians.[145] The coup attempt failed at that time[146] and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower denied any U.S. involvement.[147]

1958: Lebanon[edit]

The U.S. launched Operation Blue Bat in July 1958 to intervene in the 1958 Lebanon crisis. This was the first application of the Eisenhower Doctrine, according to which the U.S. was to intervene to protect regimes it considered threatened by international communism. The goal of the operation was to bolster the pro-Western Lebanese government of President Camille Chamoun against internal opposition and threats from Syria and Egypt.[citation needed]

1959-1963: South Vietnam[edit]

In 1959 a branch of the Worker's Party of Vietnam was formed in the south of the country and began an insurgency against the Republic of Vietnam with the support of North Vietnam.[148] They were funded through Group 559m which was formed the same year and sent weapons down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[149] In 1959 the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF) (commonly referred to as Viet Cong, literally 'Vietnamese Communist') was formed in the south, engaging in communist insurgency through the Liberation Army of South Vietnam (LASV).[150] The US supported the RoV against the communists. After the 1960 US election, President John F. Kennedy became much more involved with the fight against the insurgency.[151]

From mid-1963, the Kennedy administration became increasingly frustrated with South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem's corrupt and repressive rule and his persecution of the Buddhist majority. In light of Diem's refusal to adopt reforms, American officials debated whether they should support efforts to replace him. These debates crystallized after the ARVN Special Forces, which took their orders directly from the palace, raided Buddhist temples across the country, leaving a death toll estimated in the hundreds, and resulted in the dispatch of Cable 243 on August 24, 1963, which instructed United States Ambassador to South Vietnam, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., to "examine all possible alternative leadership and make detailed plans as to how we might bring about Diem's replacement if this should become necessary". Lodge and his liaison officer, Lucien Conein, contacted discontented Army of the Republic of Vietnam officers and gave assurances that the US would not oppose a coup or respond with aid cuts. These efforts culminated in a coup d'état on November 2, 1963, during which Diem and his brother were assassinated.[152] By the end of 1963 the Viet Cong switched to a much more aggressive strategy in fighting the Southern government and the USA.

The Pentagon Papers concluded that "Beginning in August of 1963 we variously authorized, sanctioned and encouraged the coup efforts of the Vietnamese generals and offered full support for a successor government. In October we cut off aid to Diem in a direct rebuff, giving a green light to the generals. We maintained clandestine contact with them throughout the planning and execution of the coup and sought to review their operational plans and proposed new government."[153]

1959: Iraq[edit]

Richard Sale of United Press International, citing Adel Darwish and other experts, has reported that the October 1959 assassination attempt on Iraqi Prime Minister Abd al-Karim Qasim involving a young Saddam Hussein and other Ba'athist conspirators was a collaboration between the CIA and Egyptian intelligence.[154] Bryan R. Gibson has challenged the veracity of Sale and Darwish, citing declassified documents that indicate the CIA was blindsided by the timing of the assassination attempt on Qasim and that the National Security Council "had just reaffirmed [its] nonintervention policy" six days before it occurred.[155] Although the assassination attempt failed after Saddam (who was only supposed to provide cover) opened fire on Qasim—forcing Saddam to spend more than three years in exile in the Egyptian-led United Arab Republic (UAR) under threat of death if he returned to Iraq—it led to widespread exposure for Saddam and the Ba'ath within Iraq, where both had previously languished in obscurity, and later became a crucial part of Saddam's public image during his tenure as President of Iraq.[156][157] It is possible that Saddam visited the U.S. embassy in Cairo during his exile.[158] A former high-ranking U.S. official told Marion Farouk–Sluglett and Peter Sluglett that Iraqi Ba'athists, including Saddam, "had made contact with the American authorities in the late 1950s and early 1960s."[159]

1959-2000: Cuba[edit]

The CIA backed a force composed of CIA-trained Cuban exiles to invade Cuba with support and equipment from the US military, in an attempt to overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The invasion was launched in April 1961, three months after John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency in the United States. The Cuban armed forces defeated the invading combatants within three days.

Operation MONGOOSE was a year-long U.S. government effort to overthrow the government of Cuba.[160] The operation included economic warfare, including an embargo against Cuba, "to induce failure of the Communist regime to supply Cuba's economic needs," a diplomatic initiative to isolate Cuba, and psychological operations "to turn the peoples' resentment increasingly against the regime."[161] The economic warfare prong of the operation also included the infiltration of CIA operatives to carry out many acts of sabotage against civilian targets, such as a railway bridge, a molasses storage facilities, an electric power plant, and the sugar harvest, notwithstanding Cuba's repeated requests to the United States government to cease its armed operations.[162][161] In addition, the CIA planned a number of assassination attempts against Fidel Castro, head of government of Cuba, including attempts that entailed CIA collaboration with the American mafia.[163][164][165]

1960s[edit]

1960–1965: Congo-Leopoldville[edit]

Patrice Lumumba was elected the first Prime Minister of the Republic of Congo, now the Democratic Republic of Congo, in May 1960, and in June 1960 achieved full independence from Belgium. Belgium started supporting separatist movements in the country against him, in order to keep power over resources in the region, starting the Congo Crisis. Lumumba called in the United Nations to help him, but the U.N. force only agreed to keep peace and not stop the separatist movements. Lumumba than agreed to receive help from the USSR in order to stop the separatists, worrying the United States, due to the supply of uranium in the country. At first, The Eisenhower Administration attempted to poison him with his toothpaste, but this was abandoned.[166] The United States encouraged the Belgians and Mobutu Sese Seko, a colonel in the army, to overthrow him which they did on September 14, 1960. After being locked in prison Mobutu sent him to Katanga, one of the areas launching an insurgency, and he was executed soon after on January 17, 1961.[167]

After Lumumba was killed and Mobutu Sese Seko took power the United Nations forces started acting with stronger hand and attacking the separatist forces. As well the US began funding him in order to secure him against the separatists and opposition. After his assassination, many of Lumumba's supporters went to the Eastern part of the country and formed the Free Republic of the Congo with its capital in Stanleyville in opposition to Mobutu Sese Seko's government. The government was limited in its recognition, and the United Nations recognized the government in Leopoldville. Eventually, the government in Stanleyville agreed to rejoin with the Leopoldville government under the latter's rule.[168][169] However Lumumba's former supporters felt that they had been cheated out. In 1963 the Lumumba supporters again formed a separate government in the east of the country and launched the Simba rebellion. The rebellion had support from the Soviet Union and many other countries in the Eastern Bloc. However ideological infighting and incompetence hampered its success. As well the Soviet weapon shipments shipped through Sudan were attacked by Anyanya insurgents, and when this came to light the US used this to justify supplying the Leopoldville government more.[170][170] The US and Belgium launched Operation Dragon Rouge to suppress the rebellion and were very successful. The US also supplied the Anyanya insurgents and worked with them to fight the Simba rebels.[171] As well the Kwilu rebellion also occurred in solidarity with the Simba rebellion and was also crushed.[172]

Later on after the March 1965 elections, Mobutu Sese Seko launched a second coup with the support of the US and other powers. Mobutu Sese Seko claimed democracy would return in five years and he was popular initially.[173][173] However, he instead took increasingly authoritarian powers eventually becoming the dictator of the country.[173] He renamed the country Zaire in 1971.

1960: Laos[edit]

On August 9, 1960, Captain Kong Le with his paratroop battalion seized control of the administrative capital city of Vientiane in a bloodless coup on a "Neutralist" platform with the stated aims of ending the civil war raging in Laos, ending foreign interference in the country, ending the corruption caused by foreign aid, and better treatment for soldiers.[174][175] With CIA support, Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, the prime minister of Thailand, set up a covert Thai military advisory group, called Kaw Taw. Kaw Taw together with the CIA backed a November 1960 counter-coup against the new Neutralist government in Vientiane, supplying artillery, artillerymen, and advisers to General Phoumi Nosavan, first cousin of Sarit. It also deployed the CIA-sponsored Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit (PARU) to operations within Laos.[176] With the help of CIA front organization Air America to airlift war supplies and with other U.S. military assistance and covert aid from Thailand, General Phoumi Nosavan's forces captured Vientiane in November 1960.[177][178]

1961: Dominican Republic[edit]

In May 1961, the ruler of the Dominican Republic, Rafael Trujillo was murdered with weapons supplied by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).[179][180] An internal CIA memorandum states that a 1973 Office of Inspector General investigation into the murder disclosed "quite extensive Agency involvement with the plotters." The CIA described its role in "changing" the government of the Dominican Republic as a 'success' in that it assisted in moving the Dominican Republic from a totalitarian dictatorship to a Western-style democracy."[181][182] Juan Bosch, an earlier recipient of CIA funding, was elected president of the Dominican Republic in 1962, and was deposed in 1963.[183]

1961–1975: Laos[edit]

The United States intervened in the Laotian Civil War against the Pathet Lao communist movement of Laos headed by Prince Souphanouvong, so as to preserve the royalist faction that had been favored by the French and to destroy a Viet Cong supply line known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. In this proxy war, the two sides received major external support from the two world superpowers. The U.S. government tried to keep the war secret from the American population by having the CIA Special Activities Division (Operation Millpond, Operation Barrel Roll and Operation Steel Tiger) back the war and by using tribesmen of the Hmong people that it trained, armed and paid to wage the war.[184][185][186] U.S. military support was critical, and for example, in 1962, in the Battle of Luang Namtha, the Laotian military came close to collapse but the war effort was saved by a major U.S. effort. One of the U.S.'s foremost Laotian military leaders in the field was general Vang Pao, a Hmong leader and commander of Military Region 2 in northern Laos. The Hmong people, based primarily in an area known as the Golden Triangle, needed to transport out the opium poppy they cultivated as their primary cash crop, so Air America, a CIA front, "began flying opium from mountain villages north and east of the Plain of Jars to CIA asset Hmong General Vang Pao's headquarters at Long Tieng."[187] The Hmong "tribesmen continued to grow, as they had for generations, the opium poppy....The [heroine refinery] lab's production was soon being ferried out on the planes of the CIA's front airline, Air America."[188][189][190][191][192] The CIA never denied the allegation but asserted that trading in opium was legal in Laos until 1971 and that opium was the sole cash crop of isolated Hmong hill tribes and one of their few medicines.[193]

1961–1964: Brazil[edit]

When the president of Brazil resigned in August 1961, he was lawfully succeeded by João Belchior Marques Goulart, the democratically elected vice president of the country.[194] João Goulart was a proponent of democratic rights, the legalization of the Communist Party, and economic and land reforms, but the US government insisted that he impose a program of economic austerity. The United States government implemented a plan with the code name Operation Brother Sam for the destabilization of Brazil, by cutting off aid to the Brazilian government, providing aid to state governors of Brazil who opposed the new president, and encouraging senior Brazilian military officers to seize power and to back army chief of staff General Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco as coup leader.[194][195] General Branco led the April 1964 overthrow of the constitutional government of President João Goulart and was installed as first president of the military regime, immediately declaring a state of siege and arresting more than 50,000 political opponents within the first month of seizing power, while the US government expressed approval and re-instituted aid and investment in the country.[196]

1963: Iraq[edit]

Several sources, notably Said Aburish, have alleged that the February 1963 coup that resulted in the formation of a Ba'athist government in Iraq was "masterminded" by the CIA.[197] No declassified U.S. documents have verified this allegation.[198] Tareq Y. Ismael, Jacqueline S. Ismael, and Glenn E. Perry state that "Ba'thist forces and army officers overthrew Qasim on February 8, 1963, in collaboration with the CIA."[199] Conversely, Gibson argues that "the preponderance of evidence substantiates the conclusion that the CIA was not behind the February 1963 B'athist coup."[200] The U.S. offered material support to the new Ba'athist government after the coup, despite an anti-communist purge and Iraqi atrocities against Kurdish rebels and civilians.[201] Because of this, Nathan Citino asserts: "Although the United States did not initiate the 14 Ramadan coup, at best it condoned and at worst it contributed to the violence that followed."[202] The Ba'athist government collapsed in November 1963 over the question of unification with Syria (where a rival branch of the Ba'ath Party had seized power in March).[203] There has been a great deal of academic discussion regarding allegations from King Hussein of Jordan and others that the CIA (or other U.S. agencies) provided the Ba'athist government with lists of communists and other leftists, who were then arrested or killed by the Ba'ath Party's militia—the National Guard.[204] Gibson and Hanna Batatu emphasize that the identities of Iraqi Communist Party members were publicly known and that the Ba'ath would not have needed to rely on U.S. intelligence to identify them, whereas Citino considers the allegations plausible because the U.S. embassy in Iraq had actually compiled such lists, and because Iraqi National Guard members involved in the purge received training in the U.S.[205][206][207] U.S. official Robert Komer wrote to President John F. Kennedy on February 8, 1963 that the Iraqi coup "is almost certainly a net gain for our side... CIA had excellent reports on the plotting, but I doubt either they or UK should claim much credit for it."[208]

1964: Chile[edit]

During the 1964 Chilean Presidential Elections the United States through the CIA funneled approximately $2.6 million for Eduardo Frei Montaiva, and also funneled money to help pro-Christian Democratic groups and funding propaganda to harm the reputation of Salvador Allende, the opposition candidate and Marxist. The funding made up more than half of Frei's campaign money. As well as propaganda the CIA also helped with polling, voter drives, and voter registration. The United States was doing this in order to counter the Soviet Union's support of Allende.[209] This involvement was later revealed by the Church Committee in 1975.[210]

1964-1975: Vietnam[edit]

The United States had troops placed in Vietnam since the end of World War II.[citation needed] As the First Indochina War ended with a French withdrawal, US involvement increased. This culminated in The Gulf of Tonkin incident on August 2, 1964 in which the U.S. and North Vietnamese allegedly skirmished.[211] The circumstances have been questioned since. A second attack was reported on August 4 however a declassified National Security Agency (NSA) document revealed that there no second attack.[212] This caused Congress to pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution on August 7, 1964 authorizing Lyndon Johnson "to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression". The United States expanded involvement and began to use aerial bombardments.[213] The U.S. fought a guerilla war against the Viet Cong, which was not very successful. In early 1968 the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese launched the Tet Offensive, hoping to overthrow the South Vietnamese government. However, the U.S. and South Vietnamese troops were able to stop them from taking it.[214] Despite the failure the American public questioned how exactly the Viet Cong could still launch a large offensive when they had been repeatedly told of the United States' progress in Vietnam, increasing anti-war sentiment.[215] The U.S. began peace talks in Paris.[216] The war became an issue in 1968 United States General Election and Richard Nixon, the Republican, ran on winning the war with a secret strategy in 1968.[217][218] Nixon than continued the fighting against Vietnam. His strategy was to scare the North Vietnamese while continuing the peace talks. Nixon was able to win reelection in the 1972 US election. However, he was still not successful in intimidating the communists and the U.S. withdrew in March 1973 after signing the Paris Accords.[219] The U.S. still gave support to South Vietnam, but this decreased over time. As the communists started a massive offensive to overrun the south, President Gerald Ford unsuccessfully tried to get congress to give financial assistance to the South. On April 30, 1975, Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, fell to North Vietnam.[220]

1965–1966: Dominican Republic[edit]

In the Dominican Civil War, a junta led by President Joseph Donald Reid Cabral was battling "constitutionalist" or "rebel" forces who advocated restoring to power the Dominican Republic's first-ever democratically elected president, President Juan Emilio Bosch Gaviño, whose term had been cut short by a coup. The U.S. launched "Operation Power Pack," a US military operation to interpose the US military between the rebels and the junta's forces so as to prevent the rebel's advance and possibly victory.[221][222] Most civilian advisers had recommended against immediate intervention hoping that the junta could bring an end to the civil war but US President Lyndon B. Johnson took the advice of his Ambassador in Santo Domingo, William Tapley Bennett, who suggested that the US intervene.[223] Chief of Staff General Wheeler told a subordinate: "Your unannounced mission is to prevent the Dominican Republic from going Communist."[224] A fleet of 41 US vessels was sent to blockade the island as the US invaded. Ultimately, 42,000 soldiers and marines were ordered to the Dominican Republic and the US occupied the country.[225]

1965–1967: Indonesia[edit]

Junior army officers and the commander of the palace guard of President Sukarno accused senior Indonesian military brass of planning a CIA-backed coup against President Sukarno and killed six senior generals on October 1, 1965. General Muhammad Suharto and other senior military officers attacked the junior officers on the same day and accused the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) of planning the killing of the six generals.[226] The army launched a propaganda campaign based on lies and riled up civilian mobs to attack those believed to be PKI supporters and other political opponents. Indonesian government forces with collaboration of some civilians perpetrated mass killings over many months. The CIA acknowledged that "in terms of the number of people killed, the anti-PKI massacres in Indonesia rank as one of the worst mass murders of the 20th Century."[227] Estimates of the number of civilians killed range from a half million to a million[228][229][230] but more recent estimates put the figure at two to three million.[231][232] US Ambassador Marshall Green encouraged the military leaders to act forcefully against the political opponents.[227] In 2017, declassified documents from the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta have confirmed that the US had knowledge of, facilitated and encouraged mass killings for its own geopolitical interests.[233][234][235][236] US diplomats admitted to journalist Kathy Kadane in 1990 that they had provided the Indonesian army with thousands of names of alleged PKI supporters and other alleged leftists, and that the U.S. officials then checked off from their lists those who had been murdered.[237][238] President Sukarno's base of support was largely annihilated, imprisoned and the remainder terrified, and thus he was forced out of power in 1967, replaced by an authoritarian military regime led by General Suharto.[239][240] Some scholars are now referring to the mass killings as a genocide.[241][242][243]

1967–1975: Cambodia[edit]

Prince Norodom Sihanouk, head of a political movement known as Sangkum that was first ushered to power by the 1955 parliamentary election, had for years kept Cambodia out of the conflicts in Vietnam and Laos by being friendly with China and North Vietnam and had integrated left wing parties into mainstream politics. However, in 1967 an uprising leftist occurred and year later the Khmer Rouge began an insurgency against the prince.[244] In 1968 the Viet Cong conducted the failed Tet Offensive. This convinced Sihanouk that the North was going to lose the war so he gravitated toward the US. It has been dubiously suggested that he allowed the US covert bombing of Cambodia in 1969.[245] Despite that Sihanouk still had some relations with the Eastern Bloc and the US wanted more power to bomb the country in order to combat the Viet Cong.

In March 1970 Prince Norodom Sihanouk was overthrown by the right wing politician General Lon Nol. The overthrow followed Cambodia's constitutional process and most accounts emphasize the primacy of Cambodian actors in Sihanouk's removal. Historians are divided about the extent of U.S. involvement in or foreknowledge of the ouster, but an emerging consensus posits some culpability on the part of U.S. military intelligence.[246] There is evidence that "as early as late 1968" Lon Nol floated the idea of a coup to U.S. military intelligence to obtain U.S. consent and military support for action against Prince Sihanouk and his government.[247] The coup succeeded in installing Lon Nol in power but further destabilized the country and ushered in the years of civil war between the right wing government in Phnom Penh backed by the United States and communist forces backed by the Viet Cong.[248][page needed]

After the coup the US had much more leeway to bomb the country which they did. The U.S. government intensified the covert bombing of Cambodia against the Viet Cong and the Khmer Rouge. Despite that the Khmer Republic was still not always informed of US operations.[249] However, the Khmer Rouge continued to fight onward and eventually took Phemn Penn and won the civil war taking the country.

1970s[edit]

1970–1973: Chile[edit]

Between 1960 and 1969, the Soviet government funded the Communist Party of Chile at a rate of between $50,000 and $400,000 annually. In the 1964 Chilean elections, the U.S. government supplied $2.6 million in funding for candidate Eduardo Frei Montalva, whose opponent, Salvador Allende was a prominent Marxist, as well as additional funding with the intention of harming Allende's reputation.[250]:38–9 As Kristian C. Gustafson phrased the situation:[251]

It was clear the Soviet Union was operating in Chile to ensure Marxist success, and from the contemporary American point of view, the United States was required to thwart this enemy influence: Soviet money and influence were clearly going into Chile to undermine its democracy, so U.S. funding would have to go into Chile to frustrate that pernicious influence.

The democratically elected President Salvador Allende was overthrown by the Chilean armed forces and national police. This followed an extended period of social and political unrest between the right dominated Congress of Chile and Allende, as well as economic warfare waged by the U.S. government.[252] As a prelude to the coup, the chief of staff of the Chilean army, René Schneider, a general dedicated to preserving the constitutional order, was assassinated in 1970 during a botched kidnapping attempt backed by the CIA.[253][254] The regime of Augusto Pinochet that came to power with the coup is notable for having, by conservative estimates, disappeared some 3200 political dissidents, imprisoned 30,000 (many of whom were tortured), and forced some 200,000 Chileans into exile.[255][256][257] The CIA, through Project FUBELT (also known as Track II), worked secretly to engineer the conditions for the coup. The U.S. initially denied any involvement however many relevant documents have been declassified in the decades since.

1971: Bolivia[edit]

The U.S. government supported the 1971 coup led by General Hugo Banzer that toppled President Juan José Torres of Bolivia.[258][259] Torres had displeased Washington by convening an "Asamblea del Pueblo" (People's Assembly or Popular Assembly), in which representatives of specific proletarian sectors of society were represented (miners, unionized teachers, students, peasants), and more generally by leading the country in what was perceived as a left wing direction. Banzer hatched a bloody military uprising starting on August 18, 1971 that succeeded in taking the reins of power by August 22, 1971. After Banzer took power, the U.S. provided extensive military and other aid to the Banzer dictatorship as Banzer cracked down on freedom of speech and dissent, tortured thousands, "disappeared" and murdered hundreds, and closed labor unions and the universities.[260][261] Torres, who had fled Bolivia, was kidnapped and assassinated in 1976 as part of Operation Condor, the US-supported campaign of political repression and state terrorism by South American right-wing dictators.[262][263][264]

1972–1975: Iraq[edit]

The U.S. secretly provided millions of dollars for the Kurdish insurgency supported by Iran against the Iraqi government.[265][266] The U.S. role was so secret even the US State Department and the U.S. "40 Committee," created to oversee covert operations, were not informed. The troops of the Kurdish Democratic Party were led by Mustafa Barzani. Notably, unbeknownst to the Kurds, this was a covert regime change action the US wanted to fail, intended only to drain the resources of the country.[267][268] The U.S. abruptly ceased support for the Kurds in 1975 and, despite Kurdish pleas for help, refused to extend even humanitarian aid to the thousands of Kurdish refugees created as a result of the collapse of the insurgency.[269][270][271]

1974-1991: Ethiopia[edit]

On September 12, 1974 Emperor Haile Selasse I of Ethiopian Empire was overthrown in a coup by the Derg, an organization set up by the Emperor to investigate the military.[272] The Derg was led by Mengistu Halie Mariam, and soon after he took power he became a Marxist–Leninist and aligned with the Soviet Union. The Derg ruled Ethiopia as a Marxist–Leninist military junta.[273] Soon after they took over a series of other rebel groups rose up to against the Derg. Some were separatist groups that wanted to not be a part of Ethiopia and others wanted to take over the Ethiopian government. The Ethiopian Democratic Union (EDU) was a conservative rebel group which composed of landowners opposed to nationalization, monarchists, and anti-Derg military officers. As well a number of other Marxist–Leninist groups fought the Derg for ideological reasons. These were the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Party (EPRP), Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF), Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement (EPDM), and All-Ethiopia Socialist Movement (MEISON). The Derg also had to contend with an invasion by Somalia.[274][275][276] These groups would receive support by the United States.[277] The Derg responded to these groups by initiating the Qey Shibir (Ethiopion Red Terror), targeted most heavily against MEISON and EPRP. Thousands were killed in the Qey Shibir.[278]

In 1987 the Derg formed the People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE), and continued fighting in the civil war. As well in 1989 the TPLF and EPDM fused and formed the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). They along with Eritrean separatists began to be victorious as the government. In 1990 the USSR stopped supporting the Ethiopian government as they were starting to collapse. The United States however continued to support the rebels.[279] In 1991 Mengistu Halie Mariam resigned and fled as the PDRE fell to the rebels.[280] Despite the fact that the US opposed him the US embassy helped Mariam escape to Zimbawbwe.[281]

1975-1991: Angola[edit]

Angola had been a colony of Portugal for hundreds of years however beginning in the 1960s the inhabitants of the country rose up in the Angolan War of Independence. In 1974 Portugal overthrew its right-wing military junta in the Carnation Revolution. The new government promised to give independence to its colonies including Angola. In 1975 Portugal signed the Alvar Agreement giving independence to Angola however the various groups started fighting one another. The People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) was a leftist group that was advancing upon the other two main rebel groups the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA) and National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). Cuba and The Soviet Union started sending in arms and troops into Angola to support the MPLA, and at the same time Apartheid South Africa sent in troops into Angola to support the FNLA and UNITA.

The United States began covertly supporting UNITA and the FNLA through Operation IA Feature. President Gerald Ford approved of the program on July 18, 1975 while receiving dissent from officials in the CIA and State Department. Nathaniel Davis, Assistant Secretary of State, quit because of his disagreement with this.[282] The funding for these organizations was headed by John Stockwell.[283] This program began as the war for independence was ending and continued as the civil began in November 1975. The funding initially started at $6 million but than added $8 million on July 27 and added $25 million in August.[284] Congress found out about the program in 1976 and condemned it. Senator Dick Clark added the Clark Amendment to the US Arms Export Control Act of 1976 ending the operation and restricting involvement in Angola.[285] Despite this CIA Director George H.W. Bush did not concede that all aid to the FNLA and UNITA had stopped.[286][287] According to Jane Hunter Israel became a middleman for continued American arms sales into Angola. During the Carter Administration the limited support for these organizations would continue. In 1978 the FNLA was depleted and defeated.[288][289] This only left UNITA headed by Jonas Savimbi. Savimbi was a former Maoist who eventually became a capitalist ideologically and made UNITA into a capitalist militant group.[290][291]

Meanwhile, in the United States the rise of the New Right saw the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency. His administration put out the Reagan Doctrine which called for the funding of Anti-Communist forces across the world to "roll back" Soviet influence. This saw the Reagan Administration support Savimbi and conservative think tanks, like the Heritage Foundation, lobbying for allowing more assistance to them. This saw the repeal of the Clark Amendment on July 11, 1985.[292] Savimbi would show his gratitude of this when he spoke at the Heritage Foundation in 1989.[293] Starting in 1986 the war really ramped up and Angola became a major proxy conflict in the cold war. Savimbi's conservative allies in the US, such as Michael Johns and Grover Norquist, lobbied for more support for UNITA.[294][295] In 1986 Savimbi came to the White House and afterwards Reagan approved the shipment of Stinger Surface-to-Air Missiles as a part of $25 Million in aid.[296][297] As well UNITA's headquarters in Jamba hosted the Democratic International, a conference of Anti-Communist leaders from across the globe.[298][299]

As the Cold War began to end the two sides started to approach each other diplomatically. After George H.W. Bush became president he continued to aid Savimbi. Savimbi began relying on the company Black, Manafort, and Stone in order to lobby for assistance. This company, as in the name, was headed by Charles Black, Paul Manafort, and Roger Stone. They lobbied the H.W. Bush administration for more assistance and weapons to Savimbi.[300] Savimbi also met with Bush himself in 1990.[301] However the MPLA and UNITA came to an agreement with the Bicesse Accords in 1991 ending US and USSR involvement in the war. This also saw South Africa withdraw from Namibia. Despite the peace the war ramped up again after the Halloween Massacre in 1992 and continued until 2002.

1977: Zaire[edit]